Last weekend I watched a documentary film called Fashion Reimagined. It’s been occupying a lot of my headspace this week for being fascinating, informative, and terrifying in equal measures.

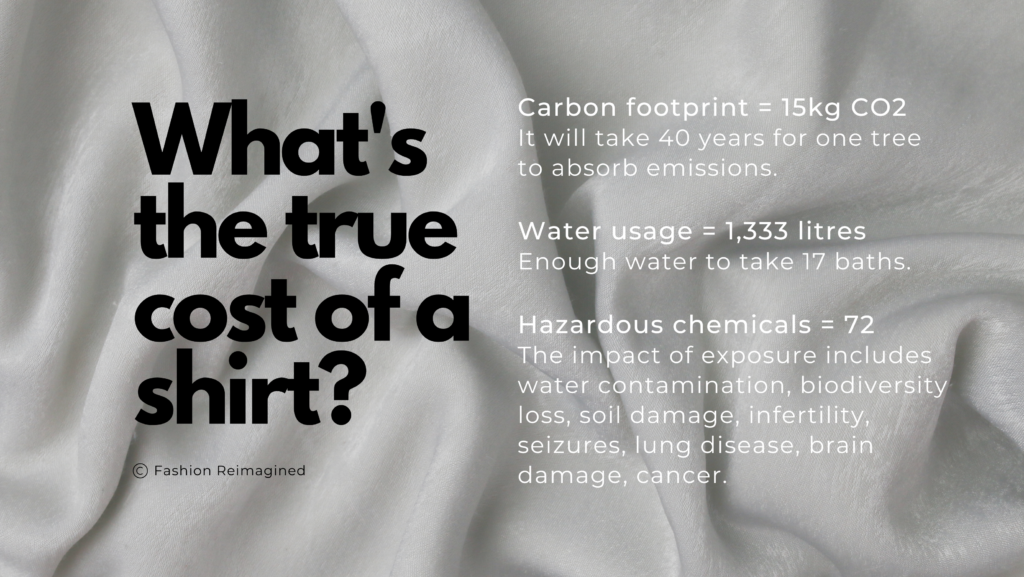

Fascinating because it gave me a front-row seat into the inner workings of an industry I don’t have first-hand experience. Informative for providing insight into what goes into creating a luxury fashion collection, giving me a newfound appreciation of craftsmanship. And terrifying when you contemplate the realities of the industry:

- If the fashion industry were a country, it would rank third for carbon emissions after China and the United States

- A typical garment travels to at least 5 countries before reaching the customer

- We buy 3 times as many clothes as we did in 1980 and wear them for half as long

- 3 out of 5 garments go to landfill within one year of purchase

- 62% of all clothing is made from synthetic materials, and 35% of ocean microplastic comes from synthetic clothes shedding in washing machines

- Traditional denim washing uses 1,500 litres of water for a single pair of jeans, the equivalent of one person’s drinking water for 2 years

- 5 out of 7 of the world’s top cotton growing countries use child labour, and an estimated 2.5 million children pick our cotton each year

- Only 2% of the people who make our clothes earn a living wage

A short synopsis for those in need; the documentary’s feature focus is Mother of Pearl (MoP), a luxury fashion house headquartered in London. Amy Powney is the creative director who sets out to explore the feasibility of creating a sustainable fashion line called No Frills, charting the story of the collection from field to finished garment. Directed by Becky Hutner, the documentary follows Amy and her team over a three-year period, as she attempts to transform her business model to become an ethical and sustainable brand.

In attempting to do so, the challenge included reimagining the house’s brand values. ‘’We completely changed our brand direction back in 2018 to put people and planet at the forefront of every choice made. Since then, our work hasn’t stopped. We continuously analyse our procedures to ensure we are at the helm of the sustainable fashion world” says Amy on the MoP website.

Shifting the status quo

Creating the No Frills line involved the brand adopting a six-point manifesto in response to some of the well-documented and egregious practices plaguing the apparel industry. The collection would be manufactured using organic materials only, the provenance of materials would be entirely traceable, production would use minimal water and chemicals, suppliers would be socially responsible, animal welfare would be non-negotiable, and have a low carbon footprint by being produced within the smallest geographical area.

What the documentary does very effectively is demonstrate just how difficult it is to be a fashion brand operating with sustainable credentials. The supply chain is riddled with inefficiency. I watched with incredulity at how natural wool was being shipped thousands of miles to be made into yarn and then shipped back again for weaving. You could count on one hand the number of vendors able to unequivocally claim compliance with the manifesto’s requirements. Even with MoP’s trimmed-down production schedule of twice-yearly collections, the shortage of suppliers able to manufacture with reasonable time-to-market would put any sustainable fashion brand out of business.

It made for depressing viewing and yet, I commend the MoP team for their resourcefulness, tenacity, and single-mindedness in pursuing their vision to reality. They got there in the end, but the rocky road never really offered them a respite.

The appetite for change

There’s a heart-breaking moment that happens in the latter half of the film. It’s buyer’s week in Paris and representatives from every major retail outlet selling luxury fashion goods are here to review collections with the intent to place orders. Having gone through the mammoth task of creating the No Frills collection in as close alignment as possible to the six core brand tenets, Amy is confronted with feedback from one of the buyer’s related to price point and the psychology of their customer:

“Sometimes the price goes up because it’s sustainable… she’s not willing to pay for it, she’s not thinking about ‘oh well this will last longer, this is better for the world, it’s OK to spend a little bit more on it’… I don’t think she gets that.”

This is not a read on the fashion buyer. I think she was just being brutally honest. There’s an undercurrent running throughout the documentary, which rightfully aims to raise awareness of the ethical and ecological issues confronting consumer fashion choices. In my view, this is the pivotal scene that perfectly puts a spotlight on what I think is the core issue.

As consumers, it highlights our collective complicity.

3 out of 5 garments go to landfill within one year of purchase

This scene was a real ‘a-ha’ moment, mentally forcing you back to this one stat presented earlier. It’s one thing to try and correct the impact of clothing on the planet before it makes it into our hands, but then how do we rationalize the aftermath of discardment?

Without wanting to sound preachy, let’s say you wear a fast fashion item a few times and it falls apart because of shoddy materials. Or you simply get bored and throw it in the trash knowing there are dozens of alternatives ready to be purchased again for a mere few dollars. Isn’t that the equivalent of raping the environment of its natural resources and then making a shameless mockery of every person being taken advantage of within that chain?

We must acknowledge that if you’re only paying a couple of dollars to purchase a piece of clothing, somewhere along the supply chain someone is getting abused. When we perpetrate a mentality of disposal income on the disposal, we exacerbate the problem. Suppliers continue to get abused, the market still gets flooded with poor quality garments, and we’ve just dropped a shedload of stuff onto the environmental dumpster with a mega carbon footprint to match.

One of the other questions I grappled with mentally is what happens if the industry develops an ethical backbone, removing fast fashion out of the picture? In the battle of choosing between sustainable versus affordable, we know where the lines are drawn. How do we make sure the economically challenged section of society who benefits from the affordable, doesn’t get left behind?

I don’t have a good answer for this. It would be very easy to namecheck the likes of BooHoo, Shein, Primark and their fast fashion competitors as the real villains within the industry. They are culpable. But like it or not, we have to accept they address a demand of our own creation. We want cheap, copycat stuff. Lots of it. The more we purchase, the more demand gets created for products that end up in landfill within the year. It takes two to tango.

When everything’s a problem, what’s the solution?

I’m clearly not a sustainability expert, but I think there’s a real reckoning that needs to happen among us consumers as we interpret our own understanding of what sustainability means. We started to see evidence of more conscious consumerism emerge in the past decade and especially during the pandemic. Withdrawing support from brands for exploitation—be it environmental, social, or due to a lack of governance, is the gateway to building a consumer movement. Taking greater responsibility requires behavioural change and amending our habits to consumerism. It means voting with our dollars.

The bigger, more challenging task is how the apparel industry can build an entire supply chain supporting sustainable practices, underpinned by strict legislation and creating circular economies where waste is minimized. It can be done. From steam powered textile mill Seidra in Austria, sustainable wool producers Lanas Trinidad in Uruguay, to Turkish Sarp Jeans who are on a mission to innovate denim production with sustainability practices, the documentary features several pioneering companies paving the way forward.

There is reason for optimism. Technology is helping reframe the thinking behind materials, with the likes of Hermes and Stella McCartney experimenting with a lab-grown, leather-like material manufactured from mycelium, the root structure found in mushrooms. Prada is using Econyl, a nylon substitute made from recycled fishing nets. Luxury accessories brands like Mulberry have initiatives in place to encourage circular fashion, as do other fashion houses investing in pre-loved resale programs. And of course MoP are creating collections using TENCEL™, a branded cellulosic fibre of botanic origin.

Marketing’s role in heralding change

Deep-rooted systemic issues within the supply chain around animal welfare, living-wage conditions, or modifying the approach to raw materials, are beyond the capabilities of any single brand or marketing team. Taking greater responsibility for the immediate problems and devoting focus to educating consumers on how a brand tackles the sustainability agenda, is wholly within our realm.

Heritage fashion brands in particular need to start thinking about how their clientele will evolve over time, what the composition of their new fashion buyer will look like, and cater towards their values. 51% of Gen Z consumers in North America do research into companies to ensure they align with their position on corporate social responsibility before purchase. 90% want the brands they buy from to get involved in causes that better the world. Paypal reports that 56% of Europeans consider themselves to be conscious consumers and 67% have bought products that were better for the environment despite being more expensive.

If we consider these stats, the effort brands commit to sustainability, inclusivity, and social justice practices has to exist beyond greenwashing and corporate activism for PR value. A mental shift is required—similar to the undertaking demonstrated by MoP in the documentary, to define the sustainability values important to the brand. It needs a vision that looks beyond deeply entrenched practices of how the business operates, along with a commitment from leadership teams to invest in adapting the brand. Change will require cross-company collaboration and cooperation across the eco-system, working with product teams, partners, and suppliers. Those who don’t fit into new world thinking should be left behind.

From a marketing standpoint, much of the practical heavy lifting will fall to product marketing, digital, and press relations teams, who will carry the responsibility of bringing initiatives to fruition. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is increasingly the domain of Marketing. It’s not uncommon for brands to appoint specialist CSR officers with expertise in innovation, social mobility, ethics, and organizational citizenship, along with a seat at the boardroom table.

Help educate your customers who are already checking your website to understand what sustainability practices your brand has in place. Raise awareness of any pre-loved shopping experiences either you or your retailers are committed to supporting. Explain how it works and why they’re important. Make fashion choices sustainable. For anyone checking clothing labels to see if materials used have been responsibly sourced or can be recycled, give them a reason to purchase from your brand. At a minimum, offer scannable QR codes to access information about the origins of the piece, sourcing practices, and why these matter to the brand. Make sure everything you claim can be backed-up.

One small leap

As simplistic as some of these initiatives may appear to be, there’s a bigger picture here at play contributing to a shift in mindset. Helping consumers develop an appreciation for craftsmanship and the importance of quality are essential to nurturing long-term thinking. Our fashion choices should be seen as an investment. And if we can’t buy better, we can always buy less in an effort to adopt a new psyche.

Ultimately however, fashion brands need to soul search their responsibility in this equation, hold themselves and their suppliers accountable, and start redefining their impact on the planet. Scaling back the number of collections produced within a calendar year seems to be a good logical starting point.

The rest is on us.

And if still in doubt, let me leave you with this final thought from Fashion Reimagined:

main image credit: Mother of Pearl